Today, EdwardsStudies.com has the privilege of talking with Rob Boss about his new book God-Haunted World: The Elemental Theology of Jonathan Edwards.

Tell us a little about yourself Rob, how long have you been studying Jonathan Edwards, and how did you get interested in his works?

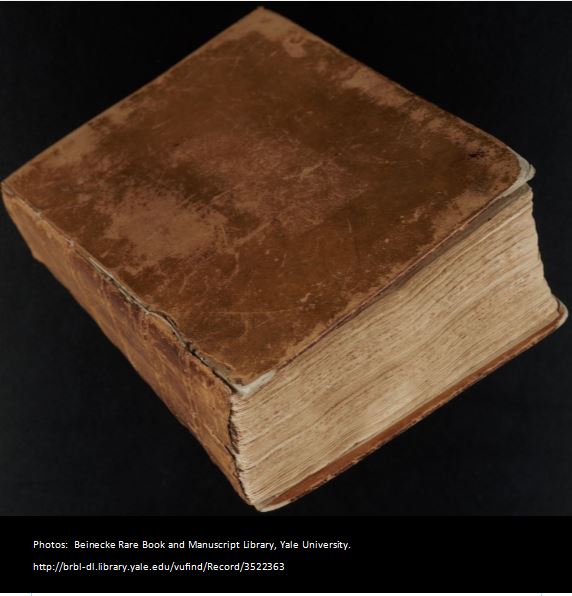

Thank you for the invitation, Matthew. My first encounter with Edwards was in 1994 while reading Michael Crawford’s Seasons of Grace: Colonial New England’s Revival Tradition in Its British Context (OUP, 1991). Soon afterward I purchased the Banner of Truth edition of Edwards’ works and began reading Freedom of the Will. It was an experience akin to drowning, but I persevered until I finished the Hickman edition of Edwards’ works. I then started collecting the Yale edition.

My interest in Edwards has been driven primarily by my experience of God’s grace. I found in Jonathan Edwards a doctor of the soul who could diagnose spiritual ailments and prescribe treatments that heal. His ability to direct persons to repentance and faith in Jesus Christ resonated deeply with me.

After pastoring a church in Oklahoma I returned to Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary for Ph.D. work in church history, where I wanted to continue my study of Edwards. It was at Southwestern that I met my dissertation supervisor, Robert Caldwell. Caldwell is a careful JE scholar who studied under Doug Sweeney and has written books on Edwards’ trinitarian theology and theology of awakening.

You scored a sweet review from Douglas Sweeney and have a recommendation from Kenneth Minkema as well. Those guys are pretty awesome in our quarters. How did you score those reviews? Have you worked with them before?

“Sweet” is an apt (and even Edwardsean) description. I am very thankful that they requested review copies of my book.

I first met Ken Minkema in October of 2007 at Northampton, MA. Under the direction of Richard Hall, a conference was convened at First Churches of Northampton on the theme of “Jonathan Edwards and the Environment.”

I presented papers at a series of Northampton conferences in 2007, 2008, and 2010. Participants included Ken Minkema, M.X. Lesser, Stephen Nichols, Rhys Bezzant, Gerald McDermott, Michael McClymond, Robert Caldwell, Oliver Crisp, and other Edwardsean scholars. It was a stimulating time to say the least.

Tell us about the title of the book God-Haunted World.

The title of the book is a story in itself. When I returned to seminary for doctoral work, I met Stephen Dempster, a noted OT scholar visiting from Canada. Though from a different field, he was full of encouragement and advice. We had a number of inspiring discussions on Edwards’ typology and natural theology. During one of our exchanges, he described Edwards’ worldview as “God-haunted” and encouraged me to write a book about it.

I registered the domain name godhauntedworld.com and began writing furiously. At the end of a couple of months, I showed my writing to Caldwell, who wisely suggested that I reduce it to 20 or so pages and submit it to a journal. Instead of submitting it for publication, I submitted it to the 2007 Northampton conference on “Jonathan Edwards and the Environment.” My paper was titled “God-Haunted World: An Edwardsean Rationale for Saving the Creation.” I soon received notice that my paper had been accepted. I was elated!

In the following years, I stuck with the “God-haunted world” theme and tried to bend my doctoral papers in that direction.

What do you mean by “The Elemental Theology of Jonathan Edwards.”

“Elemental” denotes the role of nature or the elements in Edwards’ emblematic theology.

Take us through the flow of the book. How do you progress through the content?

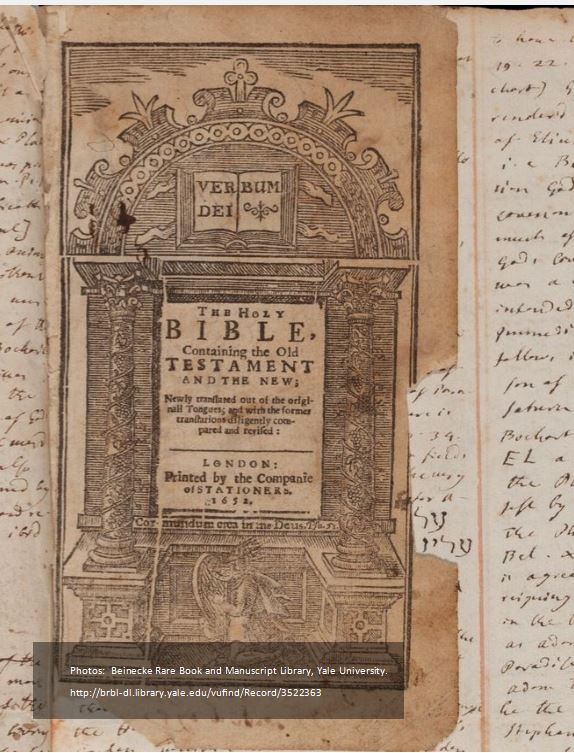

The book begins with a brief historical survey of the emblematic worldview of the Renaissance and its adoption by post-Reformation Protestants and emblem writers. I examine some emblematic works of select individuals such as Ralph Austen, John Bunyan, Benjamin Keach, Cotton Mather, and others. I then compare Edwards’ notebook “Images of Divine Things” with theirs, noting poetic quality, doctrinal content, and the primacy of Scripture over nature. I identify Edwards’ project as a reinscripturation of the world and I explore the main theological categories of his intertextual, devotional worldview.

Tell us about some of the main works of Edwards that you discuss in this book.

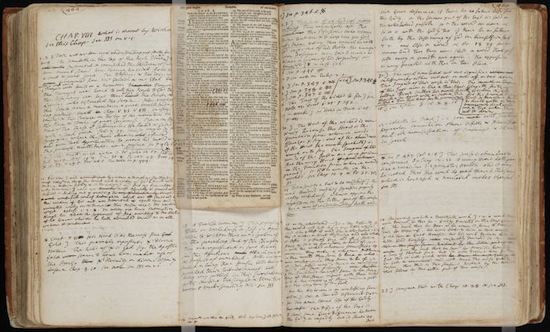

I focus mainly upon his typological notebook “Images of Divine Things,” with reference to his Miscellanies, Scientific Writings, and Sermons.

What do you want readers to capture about President Edwards, the man himself, by reading this work?

I hope that readers will better understand the meditative Edwards. I want to introduce them to Edwards’ intensely devotional, reinscripturated worldview which he summed up perfectly in “Image” no. 70,

If we look on these shadows of divine things as the voice of God, purposely, by them, teaching us these and those spiritual and divine things, to show of what excellent advantage it will be, how agreeably and clearly it will tend to convey instruction to our minds, and to impress things on the mind, and to affect the mind. By that we may as it were hear God speaking to us. Wherever we are and whatever we are about, we may see divine things excellently represented and held forth, and it will abundantly tend to confirm the Scriptures, for there is an excellent agreement between these things and the Holy Scriptures.

As I mention in the book, familiar objects such as spiders, arrows, death, sun, rain, plants, animals, and human events are transformed into powerful and affecting mental images in Edwards’ preaching and writing. The entire world is a vivid illustration of spiritual truth, truly a second book of revelation which provides powerfully affective images both comforting and frightful.

How did your research change your views about Edwards, if at all, during the process of writing?

A significant turning point in my understanding of Edwards came when I began to classify Edwards, Bunyan, and others like them as creative evangelical theologians. They believed that a poetic disposition is requisite to a proper understanding of Scripture and the world.

This is fascinating to me, especially since both E.O. Wilson and Richard Dawkins have given the poet-scientist an exalted role in properly interpreting the world. In Unweaving the Rainbow, Dawkins says that nature should inspire scientists to write poetry in order to transform worldviews. Jonathan Edwards says that creation is poetry. The difference is huge.

Reading Tibor Fabiny’s work helped me see Edwards in a wider context which included Luther, Shakespeare, emblem writers, and the English Baptist Benjamin Keach.

Writing about Edwards’ poetic worldview of similitudes and correspondences can be a frustrating exercise. One wants to see, touch, and manipulate his system of thought; at least I do. A recent breakthrough came when I started visualizing Edwards’ thought through complex network graphs. I was able to include some of these visualizations in the book, and am doing more on ElementalTheology.com.

The cover art is pretty cool. Who came up with that concept?

Full credit goes to my younger daughter, Sarah. While she was home on summer break from Wheaton College I took advantage of her artistic abilities and commissioned her to create a “new and cool” Edwards with a piercing and direct gaze. I think she nailed it. She also copy edited the book (though any remaining mistakes are entirely my own).

Have you read Oliver Crisp’s new work Edwards Among the Theologians?

I have read selections of it and am eager to finish it. His work is simply remarkable.

What are you reading right now?

In addition to the Bible, I am currently rereading Notes on Scripture, WJE, vol. 15, along with some Dostoevsky and Steinbeck.

Are you done with Edwards yet, or are you going to keep digging for future works?

There is much more to be explored … Edwards’ theology is an ocean of great breadth and immense depth.

Thanks for interviewing with us, Rob. Any parting thoughts or recommendations for readers of EdwardsStudies.com?

I leave you with a cool quote from Mark Noll’s America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln, 444.

Attentive readers of these pages will realize that if I had to recommend only one American theologian for the purposes of understanding God, the self, and the world as they really are, I would respond as the Separatist Congregational minister Israel Holly did in 1770 when he found himself engaged in theological battle: “Sir, if I was to engage with you in this controversy, I would say, Read Edwards! And if you wrote again, I would tell you to Read Edwards! And if you wrote again, I would still tell you to Read Edwards!”

Sermons

Sermons