Category: Articles

“The Excellency of Jesus Christ” (120-Second Overview)

A 120-second overview of the 1736 sermon, “The Excellency of Jesus Christ.”

Did Jonathan Edwards Inspire the Modern Missionary Movement?

This piece originally appeared at ObbieTodd.wordpress.com and is used with the author’s permission. Rev. Todd is Associate Pastor of Students at Zoar Baptist Church in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Originally from Kentucky, Obbie met his wife Kelly in the Bluegrass state and the two have been happily married since August 4, 2012. Obbie is currently a doctoral candidate in Theology at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary.

In June 1805, from Kettering, England, pastor Andrew Fuller wrote to American theologian Timothy Dwight concerning Fuller’s honorary diploma from Yale College. Fuller had attained considerable renown across the Atlantic for his treatises, owing much to the theological heritage bequeathed to him by Dwight’s grandfather, Jonathan Edwards. In this small letter, the reader discovers not only Edwards’ influence upon Fuller, but upon Fuller’s band of missionary compatriots as well: “The writings of your grandfather, President Edwards, and of your uncle, the late Dr. Edwards, have been food to me and many others. Our brethren Carey, Marshman, Ward, and Chamberlain, in the East Indies, all greatly approve of them.” The legacy of Jonathan Edwards prospered and grew in the theology and missiology of Andrew Fuller. In his defense of evangelistic Calvinism and puritanical piety, the man Charles Spurgeon called “the greatest theologian” of his century called upon the works of Edwards to meet a post-Reformation scholasticism beginning to relinquish its dedication to Scriptural principles. For all of his doctrinal and metaphysical influence, the “theologian of the Great Commandment” stirred Fuller to an even deeper spirituality with his Life of David Brainerd (1749), a biography of an American missionary to the Delaware River Indians. Fuller’s Memoirs of the Rev. Samuel Pearce (1800) bears striking resemblance to Edward’s work in many ways, giving credence to Chris Chun’s assertion that “Fuller’s main contribution was to expand, implicate, and apply Edwardsean ideas in his own historical setting.”

It is important to remember that while the two men lived in the same enlightened century, they also occupied both poles of it. Andrew Fuller was born in Soham, England in 1754: the year that Edwards’ Freedom of the Will was published and four years before Edwards’ death. Thus to say that the Congregationalist and the Particular Baptist were contemporaries would be false. However, their historical proximity was beneficial for Fuller, as he faced the same eighteenth-century rationalism as his predecessor. Edwards indeed lived on in his writings, serving to fuel Fuller’s theological aims years after his death. (Edwards’ Freedom of the Will was recommended to him by Robert Hall of Arnsby in 1775) Fuller responded forcefully to those who questioned his allegiance to Edwards: “We have some who have been giving out, of late, that ‘If Sutcliff and some others had preached more of Christ, and less of Jonathan Edwards, they would have been more useful.’ If those who talked thus preached Christ half as much as Jonathan Edwards did, and were half as useful as he was, their usefulness would be double what it is.”

Edwards’ Freedom of the Will helped him reconcile evangelistic preaching with the divine sovereignty of Calvinism. In his second edition of The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation (1801), Fuller acknowledges his debts to Edwards’ Freedom of the Will in distinguishing between natural and moral inability. In addition, Edwards not only aided Fuller in his response to the High Calvinism of John Gill and John Brine, but his Religious Affections equipped Fuller to refute Sandemanianism (“easy-believism”) as espoused by Archibald McLean. Fuller boasted that Edwards’ sermons on justification gave him “more satisfaction on that important doctrine than any human performance which I have read.”

Still, the name of David Brainerd was one Fuller held in high esteem. At Fuller’s funeral, friend John Ryland, Jr. could not help but mention Edwards’ famous biography: “If I knew I should be with…Fuller tomorrow, instead of regretting that I had endeavored to promote that religion delineated by Jonathan Edwards in his Treatise on Religious Affections and in his Life of David Brainerd, I would recommend his writings…with the last effort I could make to guide a pen.” Such a reference to Brainerd in Fuller’s funeral was apropos for a man who had served as the founding secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society since 1792. Fuller had dedicated himself to the Great Commission since his disillusionment from the Hyper-Calvinism of his childhood pastor John Eve that neglected to invite sinners to repent and believe in the Gospel. Men like Jonathan Edwards had aided Fuller in returning to the Scriptures.

It was in his last year at Soham that Fuller wrote A Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation (1786), but his removal to Kettering in 1782 would spell the beginning of a ministry set against “false Calvinism,” sparking the dawn of a movement. According to John Piper, Fuller helped initiate the first age in modern missions. (Hudson Taylor’s founding of the China Inland Mission in 1865 would begin another.) Here in the Northamptonshire Association of Baptist Churches, Fuller would meet the likes of John Ryland, Jr. of Northampton, John Sutcliffe of Olney, then a little later Samuel Pearce of Birmingham and William Carey of Leicester. Fuller’s famous relationship with Carey forged a now-legendary mission to India in which Fuller would “hold the rope” for Carey back in England. And Fuller regarded Pierce so highly that he wrote his Memoirs of the Rev. Samuel Pearce (1800) to serve as a paradigm of piety. The “seraphic Pearce” (1766-1799) has since been dubbed “the Baptist Brainerd” due to the strong correlation between the two men. According to Michael Haykin, it is important to note “Fuller’s clear indebtedness to what is probably the most popular of the American divine’s books, namely, his account of the life and ministry of David Brainerd (1718-1747).” Without a doubt, The Life of David Brainerd was a central document to the modern missions movement. Fuller began work on the Memoirs not long after hearing of Pearce’s death while on a fund-raising trip in Scotland for the Baptist Missionary Society. The news brought Fuller to tears…and action. The idea for Pearce’s biography was not a new one, but the proper window and impetus had been supplied. Fuller desired to show the world a remarkable example of Christian spirituality and support Pearce’s widow Sarah and her five children. The end product would be a biography that paralleled Edwards’ Brainerd in many ways, beginning with the very purpose it was written. For Fuller, “The great ends of Christian biography are instruction and example. By faithfully describing the lives of men eminent for godliness, we not only embalm their memory, but furnish ourselves with fresh materials and motives for a holy life.” This sounds remarkably like the beginning to Edwards’ biography of Brainerd: “I am persuaded every pious and judicious reader will acknowledge, that what is here set before them is indeed a remarkable instance of true and eminent Christian piety in heart and practice – tending greatly to confirm the reality of vital religion, and the power of godliness – that it is most worthy of imitation, and many ways calculated to promote the spiritual benefit of the careful observer.”

Important to note is that, in addition to the passionate evangelism and suffering of both Brainerd and Pearce, Fuller and Edwards both spend much of their biographies depicting the last months of their subjects – indicating that this was a significant part of the story they wished to tell. Nothing displayed Christian piety more than the passionate earthly exits of both men. And Fuller’s model clearly follows Edwards’. As Tom Nettles insightfully observes, “Intimate acquaintance with the ideas of a great theologian tends to make the student a wise and sensitive pastor. Fuller took the difficult ideas of Edwards, digested their spiritual implications and used them for the good of souls.” What the natural-moral inability distinction and religious sensibilities generated for Fuller’s polemical soteriology, the piety of David Brainerd did for Fuller’s own spiritual devotion.

Despite his never serving as an international missionary for the Baptist Missionary Society, Pearce’s zeal for evangelism is something Fuller wished to capture. Pearce once wrote to William Carey expressing his excitement at the prospect of serving with him abroad: “I should call that the happiest hour of my life which witnessed our both embarking with our families on board one ship, as helpers of the servants of Jesus Christ already in Hindostan.” Despite the vast gulf in continents, the strongest commonality between Pearce and Brainerd was their greatest mutual desire: the Gospel. Samuel Pearce stood next to William Carey on the conviction that Matthew 28:19-20 was still in effect for Christians everywhere: “I here referred to our Lord’s commission, which I could not but consider as universal in its object and permanent in its obligations. I read brother Carey’s remarks upon it; and as the command has never been repealed – as there are millions of beings in the world on whom the command may be exercised – as I can produce no counter-revelation – and as I lie under no natural impossibilities of performing it – I conclude that I, as a servant of Christ, was bound by this law.” Quotes like this one leave little doubt that the Memoirs of the Rev. Samuel Pearce packaged Fuller’s invitational Calvinism in biographical form.

With an ocean and decades between them, Brainerd and Pearce fixed their eyes upon the same target: the heathen. From an early age, Brainerd held a special place in his heart for the lost, and he pleaded with God to be sent on His behalf: “My great concern was for the conversion of the heathen to God; and the Lord helped me to plead with him for it.” Brainerd’s Godward focus continually directed him to the lost, not simply for their sake, but for his God’s: “Oh that all people might love and praise the blessed God; that he might have all possible honour and glory from the intelligent world!” Likewise, Samuel Pearce, who fought off Antinomians in his own Birmingham congregation, worked diligently to seek out those same heathen: “O how I love that man whose soul is deeply affected with the importance of the precious gospel to idolatrous heathens!”

Tom Nettles provides keen insight into the true depths of Edwards’ influence upon Andrew Fuller’s world: “Fuller and his entire circle of friends found within Jonathan Edwards the key to a peculiar theological perplexity that vexed their souls and virtually the entire Particular Baptist fellowship.” The faith and reason of the “public theologian” had emigrated from Northampton, Massachusetts to Fuller’s Northamptonshire Association, re-shaping the Great Commission for its late eighteenth-century context. While his Freedom of the Will helped Fuller reconcile the pastoral responsibility to plead for sinners and divine sovereignty to draw them, Edwards’ Life of David Brainerd served as the prototype in Andrew Fuller’s Memoirs of the Rev. Samuel Pearce, M.A. – a devotional biography meant to illustrate evangelical piety. The purpose, subject, and style of the respective biographies correlate to such a degree as to leave no doubt of Edwardean influence upon the missional thought of Andrew Fuller. In his book Andrew Fuller: Model Pastor-Theologian, Paul Brewster locates evangelism as the overarching theme of Fuller’s ministry: “Fuller’s greatest legacy among the Baptists: to support a missionary-oriented theology that helped foster deep concern for the salvation of the lost.” (106) Thanks to the life of David Brainerd and the pen of Jonathan Edwards, the modern missionary movement was born in the evangelism of Andrew Fuller.

Interview with Dr. Ken Minkema on the Forthcoming JE Encyclopedia

If you look at the back of almost any serious work on Jonathan Edwards, there is good chance that there is an endorsement given by Dr. Ken Minkema. Not only has Dr. Minkema written voluminously on Edwards himself, (including editing Vol. 14 of Edwards Works, Sermons and Discourses 1723-1729) but he also has a great knack for inspiring other Edwards scholars along the way. Dr. Minkema is executive director of the Jonathan Edwards Center and assistant adjunct professor of American Religious History at Yale Divinity School. He edits the Yale University journal and Works of Jonathan Edwards and has written or edited a number of books and articles on Edwards and other Puritans. Today, EdwardsStudies.com speaks with him about the forthcoming JE Encyclopedia project.

ES: Dr. Minkema, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to EdwardsStudies.com today. And if I may, let me also thank you on behalf of all of our readers for the many and varied ways that you and Dr. Neele (as well as your other colleagues) have expanded our field. Much respect to you both.

So tell us about the new Jonathan Edwards Encyclopedia project you have going on now. This sounds big.

KM: This has been a project that has been several years in envisioning and in the making. The new reference tools on Edwards that have come out in the last decade or more––Lesser’s Reading Edwards, a revised edition of Johnson’s Printed Writings, and most recently McClymond & McDermott’s Theology of Edwards, among other things––convinced the staff at the Jonathan Edwards Center (JEC) that it is time for an encyclopedia on Edwards to round things out. It is to serve as a go-to source for quick information on a given idea, writing, person, place, or event in Edwards’s life, along with a few sources with which a reader can follow up to further explore.

ES: Who is bringing this to publication?

KM: It is being published by Eerdmans Publishing in Grand Rapids. They have been very receptive of the idea, and have been very patient as they wait for the finished product. I think they know that these sorts of projects can take much more time than originally (perhaps overly optimistically) thought.

ES: Do you have any idea when this project will be available for readers to purchase?

KM: Well, a couple of years ago would have been nice, but we are hoping to submit the manuscript by summer 2016.

ES: Will it also be available online at the Yale Center’s site, or will it be print only?

KM: The goal is to have it in print first, followed by an online version, perhaps available by subscription or pay-per-view. That has to be worked out with Eerdmans yet. One advantage of going online with it is that we can revise and add to it.

ES: Give us an idea of how many contributors you have writing for you, as well as some of their backgrounds.

KM: We have over a hundred contributors from many walks of life, from many countries: scholars, teachers, pastors, students, retirees, bus drivers, doctors, janitors, IT personnel, you name it; there are lot of Edwards enthusiasts out there, and the response from them has been remarkable. We are very appreciative of the interest they have shown. This is very much a collaborative effort, and reflects the wonderful fellowship around Edwards. What we did was to include an online environment on our website (edwards.yale.edu) where contributors can sign up, submit their essays, receive revisions, and make final submissions. It’s a variation of community sourcing that has worked really well for us.

ES: What are some of the subjects and entries that will be covered. I know there are many, but give us just a flavor.

KM: I’ll give you the entries under “A”: Adoption (doctrine of), Aesthetics, Affections, Agency, Aging, Allegory, America, Ames (William), Angels, Anti-Catholicism, Antichrist, Antinomianism, Apocalypse, Apostasy, Appetite, Ark of the Covenant, Armageddon, Arminianism, Art, Assembly of Divines, Assurance, Atheism, Atoms, Atonement, and Awakening.

ES: It sounds like a huge editing project for someone! Who gets that pleasure to sort through all the contributions?

KM: That would be and my colleague Adriaan Neele, under the supervision of the general editor, Harry Stout. As you say, it’s huge, perhaps larger than we could have known, but it has been worth it.

ES: What do you hope this project will achieve? In other words, what impact do you hope this project will have?

KM: We would like it to serve as a quick reference tool, but also to deepen knowledge of and engagement with Edwards’s life. There are a lot of supposed “facts” that circulate that are actually inaccurate or are wrongly applied to Edwards, to members of his family, or to people he knew.

ES: Before we let you go, do you have any other recommendations or new projects that our readers could get excited about?

KM: Another community sourcing project we have is our Global Sermon Editing Project, which provides volunteers (after some training) to edit sermons by Edwards from transcripts provided by the JEC. We are always looking for new folks, so we encourage them to go to the website and sign up. Through this initiative, volunteer editors can produce (and get attribution for) an edition of a sermon by Edwards that has in all likelihood has not been read since the eighteenth century. We are also sponsoring a new monograph series, “New Directions in Jonathan Edwards Studies,” published by Vanderhoeck & Ruprecht. This series gives young scholars in particular an opportunity to get innovative work on Edwards and related topics into print. Finally, Dr. Neele and I teach a course each June at Yale Divinity School focused on a particular theme in Edwards. This year is “Edwards and the Bible.” The course is open to the public (summerstudy.yale.edu), and we would love to have folks join the conversation.

Edwards’s Funeral Sermons: David Brainerd

David Brainerd was clearly very dear to Jonathan Edwards.

The young evangelist to the native Indians, whose journal has become one of the most endearing classics of missionary devotion/biography, held a special place in Jonathan Edwards’s heart. For one, the young Brainerd had a special relationship with Edwards’s daughter Jerusha, who nursed him during his dying days. For two, Edwards edited Brianerd’s journals himself, becoming his best selling book during his own lifetime. For three, Brainerd died in Edwards’s own home and the Puritan preacher performed his funeral sermon on October 12th, 1747, three days after the young evangelist died from tuberculosis.

This funeral sermon, entitled, True Saints, When Absent from the Body, Are Present with the Lord, is contained in the Hendrickson edition of Jonathan Edwards’s sermons, and is a stellar example of a Puritan funeral sermon. Like most Puritan sermons, it was long, filled with doctrine, avoided sentimentality and superficiality at all costs (so ubiquitous in modern eulogies today), and was aimed to pierce the heart.

Edwards is working upon the text of 2 Corinthians 5:8 which says, “We are confident, I say, and willing rather to be absent from the body, and to be present with the Lord.” As with almost all sermons of Jonathan Edwards, he does not depart from his standard tripartite formulation of text, doctrine, application. So, in the opening paragraphs, Edwards gives a brief contextual analysis from the Apostle Paul’s Corinthian correspondence. In so doing, Edwards reminds his hearers of the Apostle’s own courage in facing both danger and death in order to bring the Gospel to places where it has yet to be heard. Edwards’s own hearers would have no doubt made immediate connections to Brainerd’s own life and ministry among the Indians.

From this, Edwards deduces the following doctrine: “Departed souls of saints go to be with Christ in the following respects…” Then Edwards gives several implications including: “they go to dwell in the same abode with the glorified human nature of Christ” (p. 417); “the souls of true saints, when they leave their bodies at death, go to be with Christ, as they go to dwell in the immediate, full and constant sight or view of him” (p. 420); “departed souls of saints are with Christ, as they enjoy a glorious and immediate intercourse and converse with him” (p. 422) and a few others.

What Edwards is trying to do here, approaching from multiple angles, is to assure his hearers that those who have been converted to Christ, do immediately and without hindrance go directly into the blessed and glorious presence of Jesus Christ, the God-Man, who reigns in Trinitarian splendor with the Father and Spirit. There is no waiting. There is no delay. There is no place of purgation (contra: Roman Catholicism). After death, comes the blessed state.

As he gives this great assurance, Edwards ruminates on one of his favorite theological doctrines: the Beatific Vision. This is the concept that Heaven largely consists of a joyous, active, gazing upon the eternal beauty, majesty, and wonder of the divine nature of Jesus Christ. Far from “eternally green golf courses” and cartoonish views of heaven as clouds, harps, and halos, Edwards reveals the very thing that makes Heaven so heavenly – Christ is gloriously, dominantly, present.

He says,

Their beatifical vision of God is in Christ, who is that brightness or effulgence of God’s glory, by which His glory shines forth in Heaven, to the view of saints and angels there, as well as here on earth. This is the Sun of righteousness, that is not only the light of the world, but is also the sun that enlightens the heavenly Jerusalem; by whose bright beams it is that the glory of God shines forth there, to the enlightening and making happy of all the glorious inhabitants. (p. 420).

In this way, True Saints, becomes a joyful expression of eschatological gospel realities. Edwards makes sure his hearers know that this is not a somber occasion, but one for true rejoicing for God’s people. He stocks the sermon with language of “Christ’s kingly majesty,” “ineffable delight,” and “infinite complacence.”

By way of application, Edwards looks to the gifts and graces that Brainerd had which showed his own longing for Heaven most clearly. We note that it is not until late in the sermon that Edwards even mentions Brainerd specifically. This sermon is more about Jesus Christ then the deceased, that much is clear. When Edwards does draw the young missionary into the view of the mourners gathered through his oratory, he shows many of the ways that Brainerd lived in such a manner as to bring the heavenly Beatific Vision into better perspective through the missionary’s mortal pilgrimage here on earth.

He mentions several things in particular: Brainerd’s natural talents of mind and social disposition, his extraordinary piety as a lover of Jesus Christ, and especially his willingness to endure loss and hardship for the sake of the Gospel. In one place, Edwards extols,

He in his whole course acted as one who had indeed sold all for Christ, and had entirely devoted himself to God, and made his glory the highest end, and was fully determined to spend his whole time and strength in his service (p. 439).

By this point, many hearers in the congregation (not to mention modern readers) have not only heard a good bit about Heaven, but in a uniquely Edwardsean way were able to “see” and “taste” it. Not only that, but they have been given an example of a man (Brainerd) who lived in such a way through his selflessness and sacrifice that those beauties and joys were shown manifestly in his life.

Edwards then concludes the sermon with a post-script. In this portion, (noted separately on pages 444 – 448 of the Hendrickson edition), Edwards gives a fuller treatment of the details of Brainerd’s life than he was able to do in the main portions of the spoken sermon.

John Erskine & Jonathan Edwards: Truth Unified An Ocean Apart

The following article is used with permission by the author from his own website, tobyeasley.org. Dr. Toby Easley (D.Min., Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary), is a theologian, author, and independent speaker who has twenty-nine years of public speaking and instructional experience.

John Erskine was Scottish born seven years after the Colonial American Jonathan Edwards but their life spans would end up differing by more than twenty-seven and half years. However, the years of their lives that juxtapose from 1721 to 1758, eventually kindled a true kindred spirit through Edwards’s writings on the American spiritual awakening and Erskine’s generosity to send European books.

Erskine was born into a family that had financial means and many expected him to follow his father in a life’s vocation of jurisprudence. Nevertheless, he sensed the calling of God upon his life to enter the ministry and focus on the eternal realm. According to Jonathan Yeager, Erskine’s preaching differed from Edwards by simplifying “his sermons in the manner that the leading rhetorician George Campbell taught: to use only a few subordinate points to support one main argument…As opposed to many former Calvinist divines, Erskine did not ramble on in his discourses, using intricate and hard-to-follow metaphysical assumptions.”

Erskine was born into a family that had financial means and many expected him to follow his father in a life’s vocation of jurisprudence. Nevertheless, he sensed the calling of God upon his life to enter the ministry and focus on the eternal realm. According to Jonathan Yeager, Erskine’s preaching differed from Edwards by simplifying “his sermons in the manner that the leading rhetorician George Campbell taught: to use only a few subordinate points to support one main argument…As opposed to many former Calvinist divines, Erskine did not ramble on in his discourses, using intricate and hard-to-follow metaphysical assumptions.”

As the 1740’s passed and the early 1750’s brought many trials into Edwards’s life, Erskine served as a means of encouragement through the letters they exchanged. Edwards shared many of the details of his ejection from his Northampton pulpit and his concerns for the future of his entire family. All throughout these difficult years, Erskine remained a faithful friend, correspondent, and crucial supplier of books that would have otherwise been unavailable to Edwards. Yeager also accurately claimed, “Since the number of bookshops in America paled by comparison to Britain, Edwards benefited from a patron who resided near a publishing epicenter like Edinburgh.”

Although Erskine and Edwards realized many of the intellectual ideas coming out of Europe were contrary to theirs, both men desired to read the conflicting doctrines. Erskine certainly had the intellectual capacity to think and speak against doctrinal error but Edwards could also wield the pen as an apologist and polemicist! Edwards was not only concerned about the doctrinal tremors at Harvard and Yale, he was becoming more aware of the doctrinal shift throughout Europe. After pastoring for almost two and a half decades in Northampton, he had reason for concern regarding the younger generation and the doctrinal movement within the Congregational Churches. On July 5, 1750, Edwards wrote a letter to Erskine and in sadness expressed, “I desire your fervent prayers for me and those who have heretofore been my people. I know not what will become of them. There seems to be the utmost danger that the younger generations will be carried away with Arminianism, as with a flood.” Bit-by-Bit, his prophetic words came true regarding the abandonment of Reformation Theology, and acceleration toward an Arminian majority in the two centuries following his death.

Erskine on the other side of the Atlantic lived into the early nineteenth-century and continued to impact theological discussions. During his ministry as a younger man he had stood against the Arminian principles of Wesley, and warned the Scottish people against his Methodist soteriology. Erskine’s influence within Scotland during the Eighteenth-century helped preserve the Calvinistic soteriology among Presbyterians and stifled the growth of Wesley’s Methodist groups inside Scotland. Although Erskine and Edwards lived on separate continents and ministered across the Atlantic Ocean from one another, they both had the foresight to discern the doctrinal changes of the Enlightenment and its far-reaching effects.

A Faithful Proclaimer of God’s Word: Jonathan Edwards (David P. Barshinger)

This article originally appeared at the official website of Credo Magazine on April 12, 2016. It is reprinted here at EdwardsStudies.com with permission.

The full article can be found in the new print edition of Credo Magazine entitled, “Preach the Word: Preachers Who Changed the World.” David Barshinger (Ph.D., Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) is an editor in the book division at Crossway, and has taught as an adjunct professor at Trinity International University and Trinity Christian College. He is the author of Jonathan Edwards and the Psalms: A Redemptive-Historical Vision of Scripture.

***

Dangling like a spider over tongues of fire. Standing before floodgates holding back furious waters. Targeted with an arrow waiting to be drunk with your blood. These images of the sinner’s condition have both captivated and horrified listeners and readers ever since Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) preached his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” in the hot summer of 1741. Those who heard him give this sermon in Enfield, Connecticut, on July 8 of that year became so terrified that they screamed out in the middle of it, “Oh, I am going to Hell,” and “What shall I do to be Sav[e]d?” Their shrieking forced Edwards to stop preaching so he and the other pastors present could minister to the congregation.

While perhaps the most dramatic response to one of his sermons that Edwards ever encountered, this event was just one in a long preaching ministry stretching from 1720 to 1758. Edwards would eventually be remembered more for his contributions to theology, yet his preaching played an important role in promoting revival in his congregation and throughout New England.

Aiming at hearts

The common depiction of Edwards is that of a stilted, rigid, wig-wearing figure reading his sermons in a monotone voice that lulled his listeners to sleep. Edwards was certainly no George Whitefield (1714–1770)—Edwards’s younger contemporary and the far better known preacher of the day—but the evidence suggests a more complicated picture than this caricature portrays.

During his first years in Northampton, Massachusetts, Edwards served as an assistant to his grandfather, Solomon Stoddard (1643–1729), a well-respected pastor who called preachers to deliver their sermons without notes. For years Edwards felt slightly embarrassed that he could not manage to preach without writing his sermons out in full. Over time, though, Edwards loosened up, inspired in large part by a local visit from none other than Whitefield. After seeing Whitefield’s effect on his congregation—and feeling it himself (Edwards was brought to tears at his preaching)—Edwards worked harder at preaching extemporaneously, to the point that by the end of his career, he was often speaking from bare outlines.

Ultimately, Edwards preached to the hearts of his listeners, and he understood that how he delivered his sermon played a role in reaching them. As he explained in Religious Affections, Edwards believed that one of the main reasons God ordained the preaching of his Word was “the impressing divine things on the hearts and affections of men.” And he defended “an appearance of affection and earnestness in the manner of delivery” so long as it was “agreeable to the nature of the subject” and affected the listeners “with nothing but truth.” Edwards thus devoted himself to the earnest preaching of truth that penetrated the heart. …

2014 Jonathan Edwards Conference in England

Here are all the talks from the 2014 Jonathan Edwards Conference in England.

Gerry McDermott: Directing Souls: What Pastors Today Can Learn From

Edwards’ Ministry

With questions

Without questions

William Schweitzer: Faithful Ministers are Conduits of the Means of Grace

With questions

Without questions

Stephen Nichols: Edwards and the Bible

With questions

Without questions

Roy Mellor: When the Road is Rough: Staying With What Matters Most

With questions

Without questions

Douglas Sweeney: Edwards on the Divinity, Necessity, and Power of the Word

of God in the World

With questions

Without questions

Michael Brautigam: Our God is an Awesome God: Sharing Jonathan Edwards’

Vision of God’s Excellencies

With questions

Without questions

Nicholas Batzig: Jonathan Edwards: Preaching Christ in the Song of Songs

With questions

Without questions

All Speakers: Panel Discussion

Kevin Bidwell: Morning Devotions Day 1

Without hymns

With hymns

Eric Alldritt: Morning Devotions Day 2

Without hymns

With hymns

William Macleod: Sermon on Revival

Full service

Reading and sermon only

Jonathan Edwards’s “Observations on the Trinity” (Synopsis)

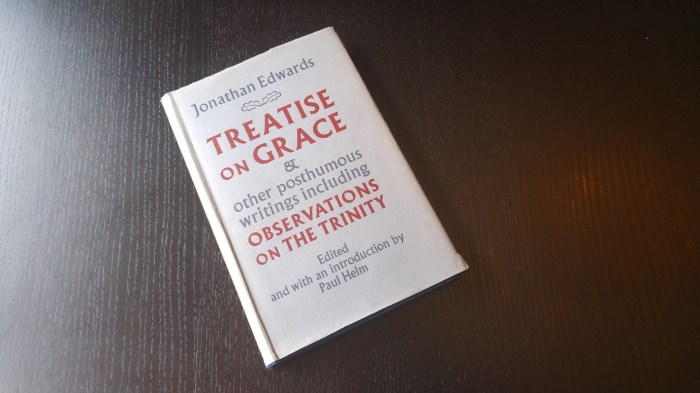

Observations on the Trinity is not to be confused with Jonathan Edwards’s other short piece on the godhead, entitled An Essay on the Trinity, although readers are likely to confuse them easily for two good reasons.

For one, they are both housed under the same roof – both short works come in the 1971 edition of Treatise on Grace & Other Posthumous Writings, edited by Paul Helm. For two, both essays are about the same size in length (the former is only 17 pages, the latter a little more at about 30). For this reason, when people mention “that little essay Edwards wrote about the Trinity,” even some of the most advanced Edwards scholars need to take a step back and say to themselves “Wait, which one is that again?”

I’ve already written on An Essay on the Trinity here. So I won’t recover that ground again, other than to simply say that this slightly longer work focuses on the persons of the Trinity in relation to one another. Edwards uses the so-called psychological model to describe how the persons can be one, and yet distinct. Edwards says that the Father is “God in the prime,” the Son is God’s perfect knowledge of Himself, and the Holy Spirit is God’s joy between the Father and Son. Each person is fully divine and yet retains distinct person-hood in relationship to the other.

In Observations, Edwards is more concerned with the economical (note: he spells it “oeconomical”) relationship between the Three Persons. Thus, it is fair to summarize both by saying that An Essay is about the doctrine of the ontological Trinity (God’s nature in being) and Observations is about the doctrine of the economical Trinity (the relationship between the Three Persons in terms of role and service to one another).

Observations begins with a fairly straightforward statement:

“There is a subordination of the persons of the Trinity, in their actions with respect to the creature; that one acts from another, and under another, and with a dependence on another in their actings, and particularly in what they act in the affairs of man’s redemption.” (p. 77).

This key statement sets the stage for all that follows. Like most Reformed theologians, Edwards will then argue for most of the rest of the essay that the Son is subject to the Father’s authority with respect to His role as the Redeemer of humanity. In a complementarian way, the Son is no less glorious or divine than the Father, but is subject to the Father with respect to His service as the God-Man by going on the mission to save humanity at His incarnation. Here, we must distinguish between the Three Persons’ worth (all are equal in divine splendor) and role (one submits to the other).

He says, “It is very manifest that the persons of the Trinity are not inferior one to another in glory and excellence of nature.” (p. 77). True enough. But this shared glory will be manifested in service one to the other in the saving of mankind. The Father appoints the Son (p. 81); the Son confers His Spirit upon the Church (p. 90).

With respect to the Father and Son, Edwards avers that they were already in an economical relationship of subordination before the Covenant of Redemption was made. He thinks this is quite important. Not only that, but the Holy Spirit too was economically subordinate to Father and Son before – and apart from – the Covenant of Redemption. Thus, Edwards seems reticent to consign subordination between persons merely to redemptive history. Rather, this is something “natural” to their eternal relationship with one another, and would have been so even without a plan to redeem the world.

To be clear, let’s define the term “Covenant of Redemption.” In some forms of covenant theology, God is understood to have undertaken a covenant – before the creation of the world and within the persons of the Trinity – to redeem humanity. This covenant is seen to undergird the Covenant of Grace (or: the New Covenant) mentioned in the Scriptures. In this way, Reformed thinkers (including Edwards) speak of the Father and Son making a covenant together to agree to redeem the elect. The Father sends the Son and assigns to Him the great task of being the God-Man and the atoning sacrifice; the Son willingly accepts the task and consents to it freely.

He says, “It is evident by the Scripture” (here we should presume he means John 17, although he does not say so explicitly), “that there is an eternal covenant between some of the persons of the Trinity, about the particular affairs of men’s redemption” (p. 80).

Edwards sees this as an agreement, however, only between two persons, the Father and the Son. Curiously, he does not believe that the Holy Spirit was a party of the covenant (p. 92) although Edwards believes the Holy Spirit “agrees” with, it and is “concerned” with it as it relates to the glory of the Holy Trinity (p. 93).

Edwards stresses that this economical subordination existed prior to the making of the covenant, as he is zealous to preserve this fact: only the subordination of the Son of God as it pertains to His humiliation is meritorious for purchasing human redemption. Thus, Christ’s subordination to the Father does not merit our salvation in regard to the pre-covenant, natural subordination of Son to Father. If this were so, Edwards argues, then the Spirit’s subordination to Father and Son would likewise be meritorious as well, which is clearly not the case. Thus the subordination that does merit our salvation is only that which is subsequent to the Covenant of Redemption; i.e. that humiliation in the incarnation that Christ willingly and freely undertook in the covenant.

So why does all this concern Edwards? Probably three reasons stand out as to why Edwards wrote Observations on the Trinity. First, Edwards is determined to understand the interrelationships between the Three Persons of the Trinity. He is not content to merely accept mystery for mystery’s sake. Edwards tends to attempt to push the envelope of human understanding as far as he can take it. We should respect him the more for this.

Second, Edwards is also concerned to defend both the equality of the Father, Son, and Spirit in terms of worth and honor, as well as to explain how it is possible for one to serve the other in humility. Scripture, he is convinced, teaches both. Again we should agree with this notion, even if we disagree with him on some of his particulars. Why the Holy Spirit cannot be a party of the covenant is not entirely clear to this writer. Nevertheless, we are right to emulate Edwards in preserving the shared divine worth of the Three Persons while seeing biblical subordination between them.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, Edwards is always anxious to defend the great glories of the godhead in the marvelous actions of redemption to save the elect. In many ways, this is part and parcel of his entire theological project. Jonathan Edwards is transfixed on understanding, savoring,and glorying in God’s great works of redemption -even those that took place long before God created the world.

— Rev. Matthew Everhard is the general editor of Edwardsstudies.com and the pastor of Faith Evangelical Presbyterian Church in Brooksville, Florida.

Owen Strachan on the Legacy of Jonathan Edwards

In this short video, Owen Strachan talks about the series of five short introductions to the life and influence of Jonathan Edwards that he and his adviser Douglas Sweeney wrote together in 2010. These introductory booklets (about 160 pages each, compact layout) can be purchased together or separately.

If you have not yet checked out this series, the series titles consist of very short introductions to Edwards’s thought on: beauty, the love of God, the good life, true Christianity, and Heaven and Hell.